Determining Digital Literacy for Reforestation in the Mansonia Community, Sierra Leone

A blog by Sheikh Mohamed Alpha Janneh II, a Frontier Tech Hub Implementing Partner.

Read about our pilot Project Sapling’s efforts in determining data literacy.

Operating in the Digital Age

The digital revolution has changed the world as we know it. Since the arrival and incorporation of the internet and mobile phones into our everyday lives, the knowledge and skills required to use such technology have become intuitive and second nature. How often do you reach your phone to check something? Or rely on instant connectivity to problem-solve with colleagues? The above are examples of digital literacy, widely defined as, ‘the ability to navigate our digital world using reading, writing, technical skills, and critical thinking. It’s using technology — like a smartphone, PC, e-reader, and more — to find, evaluate and communicate information (Microsoft).

Globally, the application of digital tools has resulted in the improvement of information collection and dissemination, as well as connectivity. Digital solutions are being introduced to rural development programs to try and address a range of issues such as supplying weather data to farmers for improved decision-making or looking to community members to monitor project tracking.

Under the Frontier Technologies Programme, Crown Agents is partnering with the Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary and the UK-based drone company UAVAid to pilot digital tools to try and address the challenge of monitoring, reporting, and verification of community reforestation activities. The pilot, termed Project Sapling, intends to train communities to use a mobile phone application to geotag tree saplings during planting, and then use long-range drones to identify each tagged tree and map them to verify the success of reforestation programs in Sierra Leone. Project Sapling starts from the premise that long-term benefits need to be strengthened within existing community reforestation programs to provide sufficient incentives for communities to be continued stewards and custodians of their forest resources. This means making a standing tree more profitable than one that can be cut down today for timber or cooking fuel, for example.

Within the pilot, we plan to build off Tacugama’s decades of experience with reforestation programming in Sierra Leone by engaging with communities to build awareness of the importance of forest resources and conservation; supporting community leadership and implementation of reforestation from seed-to-tree; introducing and supporting alternative livelihood programs; and engaging in technical skill building for community members to act as eco-guards. Tacugama’s model of community reforestation addresses short-term incentives through the direct employment of community members to conduct seed collection, nursery establishment and maintenance, and tree planting. Medium-term incentives are addressed through alternative livelihood programming such as ecotourism or utilization of non-timber forest products. For the longer-term incentives, Tacugama intends to build on the learning of this pilot to lower the barrier to entry into the voluntary carbon market so that community members can benefit from the payment to maintain high-quality carbon credits.

Notably, we want to address the lack of transparency and reliability in monitoring and tracking the investments made in forest carbon programs through the learning generated during this pilot. To do this, we intend to merge the data from the above-mentioned phones and the drones into a Geographic Information System (GIS) platform to allow for the mapping and monitoring of growth down to the individual tree. The idea is for the data to be open source and accessible globally to enable virtual inspections that will enable project managers to verify activity on the ground that can be used to increase transparency, reduce investor hesitancy and encourage investment in reforestation initiatives.

The Question Before Us — Digital Literacy in Context

However, the success of introducing a new tool into a program can live or die with the target community’s adoption of the technology with digital literacy being a key factor of consideration. In many countries, including Sierra Leone, unequal access to cell phone penetration and network coverage means that the benefits of digitalization are not fully realized. Access to, and familiarity with, telecommunications could impact a community’s digital literacy levels and whether a mobile phone app is the right technology solution to pilot. While our partner, UAVAid, was in the UK testing whether the drones could provide sharper images with more detail than commercial satellite data, we were assessing the feasibility of the community-level mobile phone app.

Figure 1. Project Sapling Target Area: the Mansonia Community. Source: Google Maps. March 8, 2023

To do so, we decided to work with the pre-selected Mansonia Community in the Loma Mountains region of eastern Sierra Leone (Figure 1). Their intended role in the pilot was to conduct the reforestation activities; test the mobile phone app and provide feedback; and allow project staff to conduct periodic monitoring and follow-up activities, including drone testing. This small farming community — mainly growing rice and groundnuts — was chosen on the basis of the success of prior community reforestation and conservation activities Tacugama had run with them. In choosing to work with a community that already had buy-in on the importance of community reforestation and its short- and medium-term benefits, we could remove that as a variable to test as part of the pilot. This enabled us to, instead, focus on piloting the digital tools that would speak to the potential longer-term benefits of reforestation programming for the carbon market. The Mansonia Community is also located adjacent to the Loma Mountains National Park, and their support of reforestation efforts increases the benefit of tree planting in the local area to help combat the encroachment of protected forest areas and critical habitat.

However, before developing the app for geotagging, we needed to understand the Mansonia community’s level of experience and comfort of using smartphones and mobile applications as a form of digital literacy — this would indicate in what ways we would need to design and tailor the mobile phone app intended to collect tree information at the time of planting.

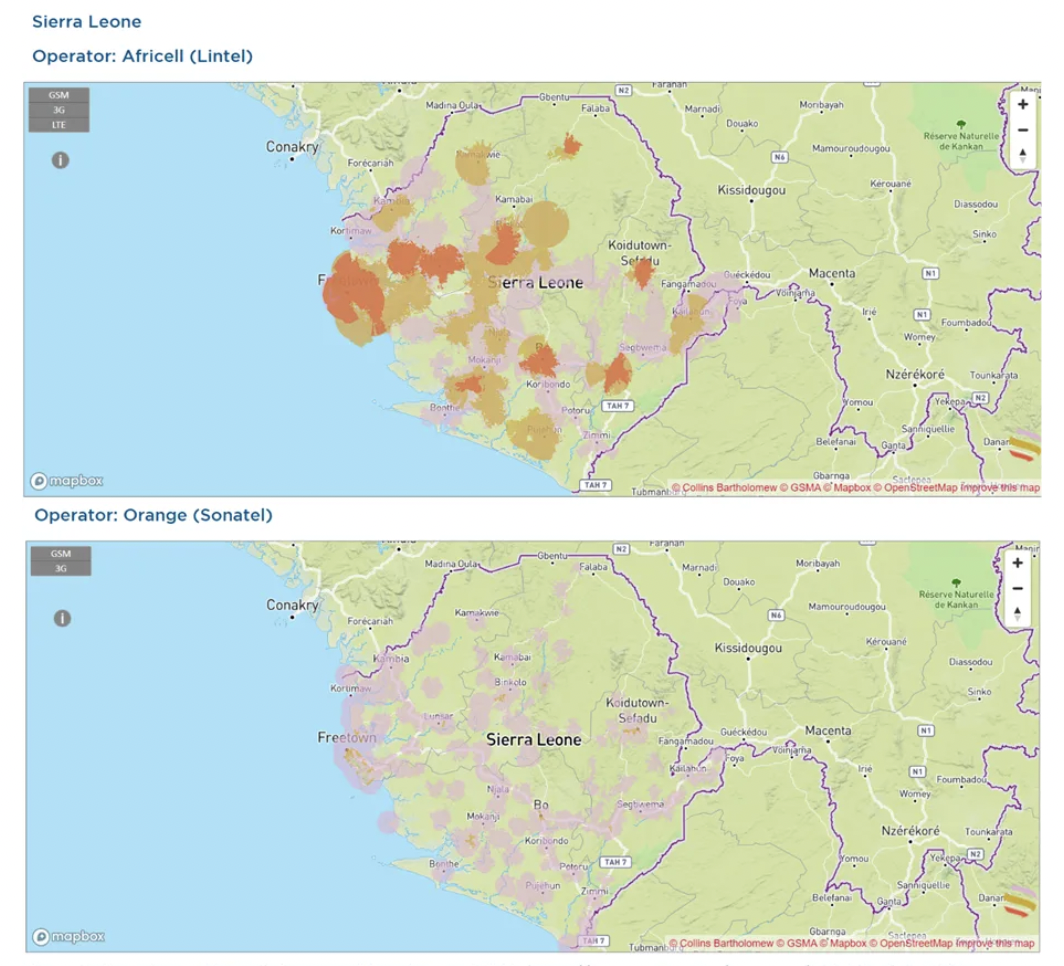

In 2021, the mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people in Sierra Leone were 98 people or 98% mobile phone penetration across the country (World Bank). However, Figure 2 shows that the location of the Mansonia community lacks cell network coverage. How might this combination of high levels of cell phone usage with low levels of network coverage influence the digital literacy within the pilot’s target groups of people and its implications for the design of the mobile app to meet the minimum required functions for data collection?

Maura Smyth and Matthew Brown assessing the live-feed of the camera system

Data literacy in the Mansonia community

To begin assessing whether our plan to build a simple, visual-based, 1–3 step application would be compatible, Tacugama conducted an informal digital literacy assessment with the Mansonia community on January 29, 2023, to:

- Assess familiarity with technology, in this case, a mobile phone.

- Gauge fluency with web-based technology given the communities network coverage levels.

- Identify opportunities to incorporate technology for reforestation relative to common mobile phone applications.

For the assessment, we used WhatsApp and asked if they would be able to conduct various tasks such as writing and sending a message; and taking, uploading, and sending a photograph. We wanted to identify their ability to read and write in English[1], their numeracy, their ability to use and follow graphical representation (e.g., icons and symbols) in a numbered sequence, and their ability and comfort level using a smartphone for writing and photography. We assumed that WhatsApp would be a useful proxy to test digital literacy levels in advance of being able to develop any beta versions of the intended mobile app for the pilot as WhatsApp is a common and readily available application within Sierra Leone and shares the key functions we anticipate needing in the intended pilot app.

We stratified the Mansonia community respondents into the three stakeholder types we anticipate primarily engaging with for the pilot. Notably:

i) senior, local leadership to support with engagement and facilitation

ii) technical supervisors to lead with sapling propagation and reforestation

iii) youth tree planters to get the saplings in the ground and geotagged

Our Results and Conclusions

The key finding resulting from those who participated is that there is no correlation between English literacy and numeracy and digital literacy and the ability to use a smartphone for the intended app functions and requirements. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the results by action, stakeholder role, and whether they had a ‘high,’ ‘medium,’ or ‘low’ level of proficiency. A high proficiency was based on whether the respondent could complete the task easily and without any assistance, the medium was if there was a minimal challenge in completing the task, and low was if the requested activity was unfamiliar to the respondent or assistance was required to demonstrate various components of the activity.

Stakeholder trends reveal that:

- Senior community leadership had low levels of literacy across the board. This, however, is not an obstacle to the project, as their primary roles and responsibilities within the project are to ensure community uptake and facilitation of the mission.

- Supervisors can read and write and can use the smartphone to take photos and upload them to another application. Supervisors can be teachers, National Protected Area Authority rangers, or community eco-guards.

- Most community members who would conduct the tree planting cannot read or write but are able to use the smartphone to take photos and upload them to another application.

A distinction was found based on age where older community members struggled with the smartphone. Younger community members, those who would be tree planters, were proficient at using smartphones, and it was also observed that younger men were better than younger women at performing the tasks. However, with enough practice, we anticipate that younger women should have no problem using smartphones.

Table 1. Results of the Informal Digital Literacy Assessment by Stakeholder

We interpret that these digital literacy results may stem from the level of cell penetration, regardless of local network coverage. The level of cell penetration has provided sufficient exposure and common use of mobile phones and common applications. Although the community senior leadership stakeholder group had low levels of digital literacy, the minimum requirement is for them to have a basic understanding of the purpose of the app, how the data will be collected, and what the data will be used for to facilitate community adoption and use of the technology. They would not be required to use it for data collection.

Next steps

These findings will inform the next steps of app development. UAVAid has incorporated these digital literacy results into a Terms of Reference for their app developer that reflects the differentiated needs of the community stakeholder groups to develop a beta version of the app. In the next sprint of the pilot, we will:

Develop the app and conduct iterative tests with the community members in advance of tree planting to determine the suitability and functionality of the app. Timing-wise, the app will need to have minimum functionality and community training and uptake before tree planting in advance of the rainy season.

UAVAid will purchase cell phones to provide the tree planters with the single-purpose app uploaded onto it for the purpose of conducting a one-time collection of sapling planting information and GPS coordinates to establish the initial data set for verification and long-term monitoring

If you’d like to dig in further…

📚 Read about the drone’s first test and the top five learning points — “Drone Mapping UK Cornwall On The Way To Africa”

📚 Explore learnings from the pilot’s field trial — “Investing In New Forests ? — How to prove trees have actually been planted.”

📚 Learn about the pilot’s recent planting event — “Transforming Sierra Leone’s Landscape: A Community Tree Planting Event Powered by Mobile App Geotagging”